History of the Site

In his 1816 report on the 'first female factory' at Gaol Green (Prince Alfred Square) the architect Francis Greenway made it clear there was a need to improve the crowded accommodation above the Parramatta goal. [1] Macquarie was prompted to ask for the report by Samuel Marsden, who, with growing dismay had complained about the disorderliness of the women convicts. He had continually written letters to the social reformers Wilberforce, Lord Bathurst, Elizabeth Fry, lobbied Governor Macquarie, and while in England in 1808, discussed the problem with the archbishop and the secretary of state. [2]

This report and Marsden’s concerns must have resonated with Governor Macquarie for in January 1817 he placed the construction of a new Female Factory building on the list of essential public buildings. In March 1817 Greenway was given orders to

… make out a ground plan and elevation of a factory and barracks sufficient to lodge 300 female convicts, on an area of ground of four acres, enclosed by a stone wall nine feet high’. [3]

As Macquarie’s favoured architect Greenway was kept extremely busy. At the beginning of 1818 Macquarie had him working on the South Head lighthouse, the government stables, the Sydney military barracks, and St Matthew’s Church (Windsor).[4] Finally a site was chosen on the north side of the Parramatta River, just up from the weir constructed for the government mill.

This site was on the original grant given to Governor Bligh, but resumed by Macquarie after Bligh’s departure under a cloud of scandal.[5] In December 1817 Major Druitt, the recently appointed Chief Engineer, called for tenders based on Greenway’s plans and specifications.[6] The contract was handed over to William Watkins and Isaac Payten in April 1818 under the condition they would complete it in eighteen months for the sum of 4778 pounds.[7] On the 9 July 1818 Governor Macquarie laid the foundation stone but the work was not finally completed until January 1821.[8]

On 1 February 1821 Macquarie and Commissioner Bigge visited the new building to watch 109 women and 71 children removed from the old gaol and lodged in the newly completed ‘Female Factory’. Bigge who was at this time conducting an enquiry into wastage of funds in the colony appears to have been less than impressed and doubted such an expensive new barrack had been necessary.[9]

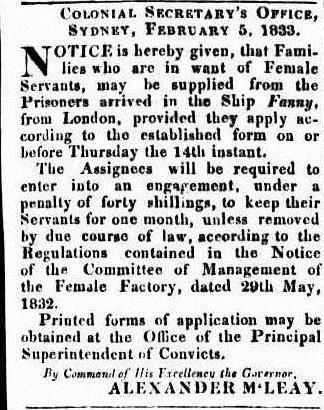

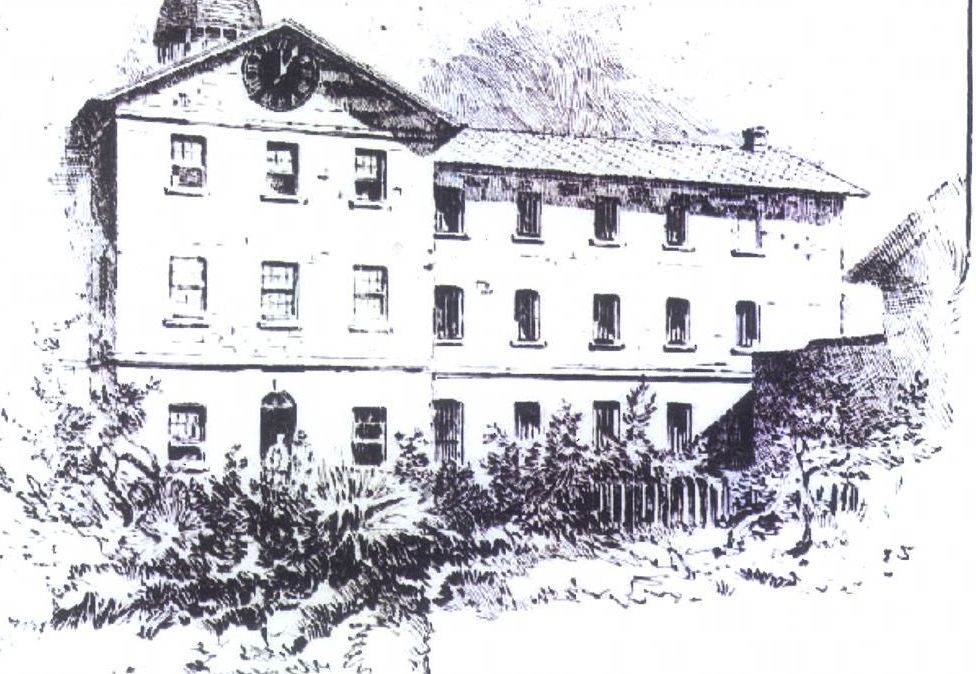

Bigge described the principle building as consisting of three stories broken into two separate wings by the central staircase and cupola which aided in ventilating the whole. On the ground floor were the dining rooms while the upper floors were for sleeping. The whole was surrounded by a wall which the main building divided into a inner and outer courtyard. Inside these yards were variety of smaller buildings used to house the administrators, a small hospital, kitchens and a room for weaving cloth. [10] A good idea of the layout of the factory can be gleaned from the maps drawn by Standish Lawrence Harris, in 1823, shortly after the building opened.[11]

This original building covered 1.6 hectares with a three story main barrack or dormitory building with single story service buildings on either side of a front courtyard. The workshop and service buildings faced into a rear courtyard where there was also access towards the river.[12] The design which was essentially simple and lacking ornament bore some similarities to the Hyde Park barracks also designed by Greenway. However one of the primary faults in the design proved to be its close proximity to the riverbank and which, as Bigge pointed out, had a breach which threatened the foundations of the wall and required a deep buttress to protect the foundations.[13] In fact the late decision to build a perimeter wall and the flood measures required to ensure the wall wasn’t washed away increased the overall costs by 1200 pounds.[14]

Parramatta Female Factory, pencil sketch, 1823, Robert Charles Harry, National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an6239017

Greenway’s ‘female factory’ was by no means the final solution and as demand, and attitudes, to convict women and medical treatment changed so did the factory and the precinct around it. One of the major faults of the original design was it did not allow for separation of different classes of convicts. This led to the modification of the stairwell to divide the first class and third areas. New workshops and a privy built on the river-side of the complex are clearly visible in the S L Harris elevation and plan of the buildings (Figure 2.23).

William Buchanan, plan of the Female Factory, November 1833. National Archives UK, formerly PRO), PRO MPH 91(9)

In 1823 Governor Brisbane added a two-story building in a separate yard to the north-west as a prison wing intended to hold 60 female convicts and hold free as well as convict women charged with crimes.[15]

Another issue was caused by that fact the ‘female factory’ in the 1820s treated most of the women in the colony that required medical attention. There was a hospital ward in the outer courtyard but surgeons treated women in the open in the courtyard. In 1829 they requested a verandah to be installed to give them some protection. The 1833 plans suggests they occupied the right hand range of buildings in the outer yard and by 1861 it appears a second story had been added. These buildings are still standing.[16]

Over the ensuing years a courtyard and surrounding buildings were modified to suit the changing needs of the administrators and inmates. Separate buildings and enclosures were erected and maintained by the Royal Engineers and in 1825 buildings were constructed for females women sentenced for crimes by the Sydney law courts. These were essentially prison accommodation for what were termed ‘third class’ inmates and who were kept separate from the other 1 and 2 class women housed in the older sections of the Female Factory.[17]

Under Governor Darling each class was provided with its own kitchens, workshops and accommodation. These were built around a series of courtyards and walls surrounding the main building. And in 1828 a pump and internal water system was installed removing the need for women to go outside to get water. At the same time the height of the wall was raised to 16 feet presumably reflecting the move toward a more prison-like precinct.[18]

In June 1838 the Royal Engineers, under Captain Barney, started work on a new building to the east of the first female factory building which would create a more punitive environment for the inmates. This was described in 1906 by Charles White, in his newspaper serial, Fifty Years Under the Lash,

In 1839 the Factory was remodelled, extensive alterations and additions being made, under the order of Governor Gipps. The number of cells was increased to seventy-two, and they were built on the plan of the American separate system. The total cost was £3767, and the Governor reported that; under a new Act that was passed for the better regulation of the female prisons, order, cleanliness, perfect obedience, and silence prevailed in the establishment to a degree scarcely surpassed in any prison in England.

[19] This three story cell-block was completed in September 1839 and although clearly built to suit its purpose of imprisoning inmates the bottom floor was criticised by Her Majesty’s Prison Inspector for being too dark. As a result new windows had to be cut into the concrete walls.[20] Gipps was clearly interested in reforming the conditions at the factory and along with the new building he also introduced two new administrators, selected by the English reformer, Elizabeth Fry. It was during this period under Governor Bourke and Governor Gipps that the factory came to be seen primarily as a prison. [21]

In 1840 transportation to New South Wales stopped and in 1841 assignment of convict women ceased to the factory ceased.[22] By 1846 there were only 250 women in the factory and the government began to move a new group of inmates into the building as it was repurposed as an asylum for the insane. By 1848 the administrative positions of the ‘female factory’ including those of matron had been abolished.[23] It was also at this time that the precinct was renamed the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum. [24]

In 1849 Dr Patrick Hill who oversaw the asylum chaired a committee to consider future locations for ‘convict lunatics’. While he suggested the ‘female factory’ could really only deal with ‘lunatics’ of one sex the rest of the institution could perhaps take 50-70 male mental health patients.[25] Hill further suggested the precinct become the institution for ‘uncurables’ of both sexes.[26]

By 1850 the Greenway designed ‘female factory’ and most of the outlying buildings were incorporated into the new insane asylum precinct. Today there you can still find some remnants of walls, courtyards and outlying buildings but sadly Greenway’s original building and the 1838-1839 penitentiary extensions were demolished in 1883 when the asylum was redesigned. The sandstone from the penitentiary extensions appears to have been used construct the James Barnet designed, ‘No. 1 Male Ward’, now the ‘Institute of Psychiatry’ building.

Patients moved into this new building in 1885 and it is still standing on the site, with the turret clock from the main ‘female factory’ building mounted in the spire.[27] Greenway’s old ‘female factory’ was deemed beyond repair for the new asylum and demolished in 1885-1886. Its stones were used for the foundations of a ‘religious services and recreational activities’ area.[28]

[for more information see our other blog posts: The First Female Factory, Prince Alfred Square, 1803 – 1821, Parramatta Hospital for the Insane, and the destruction of the female factory buildings 1878 -1983 and History of the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum 1848-1878]

Surviving Buildings

Parramatta Female Factory, Building 103, Parramatta City Council, Maribel Rosales and Sally Chik, 2015

One part which did survive, although it has undergone many modifications, was the store (building 103) originally flanking a courtyard and the superintendent’s quarters for the factory. Built between 1818 and 1821 it is currently used as the Institute of Psychiatry lecture rooms.[29] One of a pair of buildings (building 111 is the other) the north-east section had a second story added sometime around 1865. More additions were made over the course of the 1900s, including Bay windows and a porch around 1915.[30]

North Parramatta, Female Factory, Sleeping Ward’, built about 1825, photo Parramatta City Council, Peter Arfanis, 2015.

A second surviving portion, although not part of the original Greenway building, is the former prison ‘Sleeping Ward’ (building 105). Made up of two joined sections this was part of the first major extension to the factory for ‘Third Class’ female convicts and was built by the Royal Engineers around 1825. It was originally two storied with a stair-well in the south-eastern room. In 1863 a verandah was added to the western side and the upper floor was removed in the 1880s and it was around this period that gothic revival timber elements were added in an attempt to make its profile more picturesque. The second section, the north wing, was constructed around 1890 and was used as the ‘Wet and Dirty Ward No 8’.[31]

Also still in existence although heavily modified over the years is the store building which originally sat adjacent to the matron’s quarters and female factory Library. This originally featured a verandah across the entry to the courtyard. In 1865 it appears an attic was added to the single story section and the dormers still in place were completed. The two story section still retains the original stone work with bevelled details to the edges to prevent inmates climbing the walls. Side additions were added in the 1930s and 1940s and a skillion addition in the 1950s.[32]

Still surviving also is the Thwaites and Reed turret clock which was first installed in the Greenway’s original ‘female factory’ building. According to most research this clock was removed sometime around 1885 and put into the newly constructed tower of the male asylum ward. There is however some reason to question this assumption as the current turret clock has a least three faces and the old female factory only one. This would suggest the current clock is either a heavily modified version of the first or even perhaps a new Thwaites and Reed clock. We would be interested if anyone could cast more light on this as the clock remains in the clock tower to this day.

Parramatta Hospital for the Insane, Female Factory prison, sandstone blocks, courtyard wall, Parramatta City Council, Geoff Barker, 2014

Probably the most impressive section of the old female factory precinct still intact is the sandstone walls which were built around 1838, to create a walled courtyard around the central female cell block. Although these were subject to modification in the 1860s when it was used to house mental health patients. This high sandstone wall still completely encloses the space adjacent to the Roman Catholic orphan school although there obvious wear and tear obvious to some parts of the wall. The blocks themselves are all convict sandstone and each bears the individual marks of its maker.[33] The small building at the northern entrance was possibly part of the original ‘dead house’ and was probably built around the same time.[34] Sections of these walls were also rebuilt in the 1860s and in the 1880s. [35]

Another reminder of the old ‘female factory’ cited by Higginbotham and Associates in their 2010 Report is the former ‘dead house’ erected in 1838 as a small building adjacent to the entrance of the Artisan’s Yards.[36]

Hear about the experiences of the women at the Female Factory 200th Anniversary Podcast.

![]() Geoff Barker, Research and Collection Services Coordinator, Parramatta City Council Heritage centre, 2015; updated 2018

Geoff Barker, Research and Collection Services Coordinator, Parramatta City Council Heritage centre, 2015; updated 2018

References

[1] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.64

[2] A. Yarwood, Samuel Marsden, p. 188.

[3] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.18

[4] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.18

[5] Kerr, Liston, McClymont, Parramatta a Past revealed, Parramatta City Council, 1996, p.97

[6] Sydney Gazette, p.1, a, 20 Dec 1817, John McClymont (c), #13 – 3/97 – 9000 – Map

[7] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.64

[8] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 19

[9] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.65

[10] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.65

[11] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p.20

[12] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 52

[13] J Broadbent and J Hughs, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 1997, p.66

[14] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 52

[15] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 54

[16] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 56

[17] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p.21

[18] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[19] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p.21

[20] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, 2010, p.21

[21] Kay Daniels, Convict Women, Allen and Unwin, 1998, p.117

[22] Kay Daniels, Convict Women, Allen and Unwin, 1998, p.67

[23] Kay Daniels, Convict Women, Allen and Unwin, 1998, p.67

[24] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[25] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[26] Government Medical Officer Letterbook AONSW 2/676, p. 11, cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 59

[27] Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 61

[28] Weatherburn 1990, citing Annual Reports of Inspector-General of the Insane 1885 and 1886. Kass, Liston (1998) and others mix up which building was demolished and therefore which stone is the source of No 1 Male Ward, cited in Casey and Lowe, Cumberland Precinct and Sports & Leisure Precinct, 2014, 64

[29] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, 2010, p.88

[30] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, 2010, p.88

[31] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 98

[32] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 138

[33] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 154

[34] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 143

[35] Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 143

[36] T Smith, Hidden Histories, cited in Conservation Management Plan and Archaeological Management Plan, Cumberland Hospital East Campus and Wisteria Gardens, Edward Higginbotham & Associates PTY Ltd, Geoffrey Britton & Terry Kass, 2010, p. 34